The US Senate is made up of 100 Senators, two from each state. The Senate was the product of a number of compromises when the founding fathers framed the Constitution. On one hand, the Senate is meant to represent the states more so than individual citizens. Originally appointed by state legislatures, Senators have only been directly elected in most states since 1913 after the ratification of the 17th Amendment. Still, Senators are elected by entire state populations, not districts like Representatives, which makes them further removed from the interests of the individual voter, forced to represent a broader range of ideas. Senators, it was thought, would represent a more elite form of thinking, not to be swayed too quickly by the fleeting passions of the masses. Further adding to this notion was a long term of 6 years for all Senators. They rotate these terms so that one third of the Senate is up for re-election every two years. This allows for Senators to spend more time governing and less time worrying about re-election.

Also important in the compromise that produced the Senate was the debate between states with large populations and states with small populations. The smaller states like Delaware were afraid that the large states like Virginia would control a body proportioned by population and their voice would never be heard. The Senate is proportioned equally among all states regardless of population, giving the smallest states the same voice in legislation as the largest.

The Senate is also much more given to parliamentary procedure and tricks than the House. Specifically, the filibuster, though rarely used in practice, allows for any Senator to speak for as long as he would like to hold up a vote so long as the opponents cannot muster a “supermajority” of 60 votes for cloture to force a vote on the bill. This allows for minority parties to present greater opposition than their counterparts in the House but also makes it much harder to get controversial bills passed. Once again, the Senate demonstrates its tendency to moderate and slow down the legislative machine on Capitol Hill.

As we turn our eyes to the 2010 elections, it is important to understand this institutional framework of the Senate, as well as recent trends in party control. The graph below shows the share of seats among Democrats and Republicans (third parties were thrown out in order to simplify the data) since the end of the Civil War.

As you can see, despite brief periods of strong partisan control after the Civil War and the Great Depression, very modest gaps have existed between majority and minority parties. Still, there is a very clear pattern of consistent Republican majority right up until the Great Depression after which Democrats have had a significant advantage. The last 30 years, however, have been a very tight tug-of war with neither party demonstrating a clear advantage for more than three or four elections. In fact, the 2008 election gave Democrats the first supermajority since 1979.

Recent trending would suggest that Republicans should begin to see the pendulum swing back in their direction; however, this does not mean that they will regain control of the Senate. The majority party has only lost more than 5 seats three times since 1979 out of 16 elections.

This election is certainly shaping up to be an interesting one, though, with Democratic Senators retiring left and right and a Congressional approval ratings as low as 11% according to the most recent Economist survey!

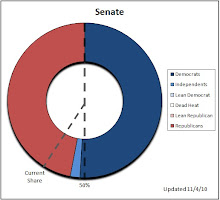

So what exactly is at stake in this election? 36 seats will be voted on in 2010, not counting the Republican victory in Massachusetts. The year began with Democrats holding 60 seats and Republicans holding 40. That distribution looked like this:

The Independents, of course, caucused with the Democrats providing them their 60 vote supermajority.

The victory of Scott Brown made the distribution 59-41 and broke the Democrat supermajority. Now, with 36 seats potentially up for grabs, the distribution looks more like this:

Obviously, Democrats still hold a significant advantage. There is enough lee-way, though, that Republicans could make a significant move.

Of the 36 seats up for reelection, it is an even split of 18 Republican and Democratic seats. An overall view of this race would not seem to indicate a favorable disposition for Republicans to make a move, but Republicans feel better about holding their seats than Democrats do about holding theirs. Over the next week, I will analyze individual races that will make or break the 2010 election for both parties. I will project a winner in each race and, after compiling them all, project the new distribution of seats in the Senate Chamber of the 112th Congress.

I will begin by taking a look at the Colorado Senate Election.

*Information obtained from various sources including Wikipedia and CongresOL.com*

No comments:

Post a Comment